The Georgia Power Paradox: Why a $15 Billion Plan Doesn't Add Up

There’s a number floating around Georgia that demands attention: $15 billion. That’s the capital Georgia Power proposes to spend on new energy projects to meet what it describes as a tidal wave of future electricity demand. In any corporate context, a nine-figure expenditure is significant. A ten-figure one is transformational. This is a bet-the-farm number, and it deserves scrutiny.

The utility’s justification is built on a single, compelling data point: approximately 80% of this projected energy surge is expected to come from data centers. This isn’t residential growth; it’s the physical manifestation of the AI boom, a cluster of power-hungry server farms demanding electrons. On the surface, the logic is linear. Demand skyrockets, so supply must be built to match. But when you dig into the specifics of how Georgia Power plans to build that supply, the neat, clean narrative begins to fray. The company’s proposal, detailed in presentations where a Georgia Power manager outlines grid investments, growth and rate freeze during Rotary talk, calls for adding 10 gigawatts of capacity, with a full 60% of that infrastructure fired by natural gas.

This is where the paradox emerges. The utility is citing an urgent, near-term demand explosion driven by a fast-moving tech sector, yet its primary solution involves investing in infrastructure with significant lead times and long-term price volatility. It raises a fundamental question for any analyst: Is this plan truly the most efficient allocation of capital to solve the stated problem, or are Georgia ratepayers being asked to finance a strategy that prioritizes the utility’s business model over their own economic interests?

The 80 Percent Question

Let’s first accept the premise. The demand from data centers is real. The question isn't whether growth is happening, but how one models the risk associated with it. Peter Hubbard, a PSC challenger with a background in energy modeling, has raised the obvious concern: what if the AI bubble bursts? What if developers simply choose to build elsewhere? If that happens, customers could be left paying for billions in stranded assets they don’t need. Georgia Power insists it has off-ramps—it could delay construction or sell excess capacity—but as Hubbard correctly notes, once you start ordering turbines and expanding pipelines, you can’t unring the bell.

I've looked at hundreds of these capital expenditure plans, and the timeline here is what I find genuinely puzzling. The utility is framing this as a response to an immediate need, yet the industry data shows that new gas turbines are facing supply chain backlogs that stretch into the early 2030s. There is a fundamental disconnect between the problem’s urgent framing and the solution’s protracted timeline. Why commit to a slow, expensive build-out when faster alternatives exist?

This leads directly to the core of the issue. According to Hubbard and other critics, Georgia is a top state for solar growth, and there are currently nearly 18 gigawatts of solar and battery projects from third-party developers seeking to connect to the state’s grid. This represents a massive pool of potential capacity (far exceeding the 10 GW the utility is planning) that could be brought online faster and, by most metrics, more cheaply than new gas plants.

The situation is analogous to a logistics company facing a sudden, massive increase in shipping demand. The company’s leadership could announce a plan to spend billions building a new fleet of proprietary cargo ships, a process that will take five to seven years. Or, it could immediately lease capacity from the hundreds of available charter vessels ready to sail tomorrow. Georgia Power is choosing to build the new fleet. The unavoidable conclusion is that the decision isn't purely about meeting demand; it’s about owning the assets that meet the demand. For a vertically integrated, regulated utility, profit is earned on the projects it builds and operates. Third-party solar, while beneficial for the grid, is simply less lucrative for the company’s balance sheet.

An Unbalanced Equation

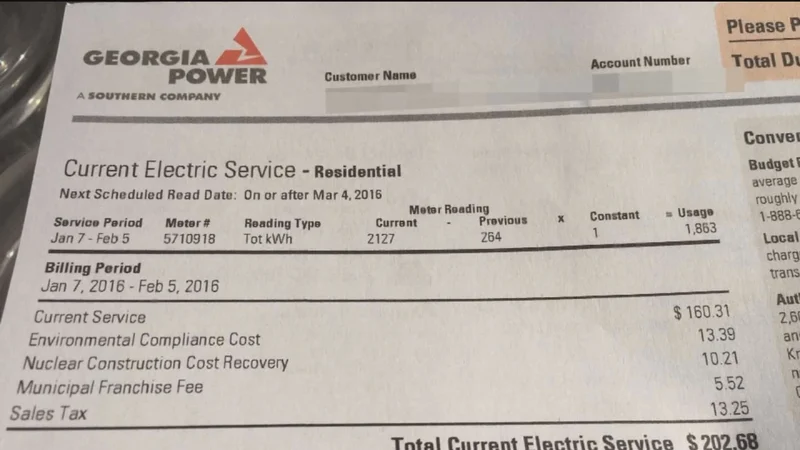

This strategic choice has direct consequences for the people paying the bills. As one report titled Energy bills are rising nationwide. In Georgia, they’re on the ballot. explains, the average Georgia Power household has already seen its monthly electricity bill jump by a significant amount in just two years—about $43, or to be more exact, a $43 increase since 2022. Much of that is attributable to the massive cost overruns from the Plant Vogtle nuclear project, a multi-billion-dollar endeavor that serves as a painful precedent for what happens when massive capital projects go off-script. The current Public Service Commission (PSC) signed off on those rate hikes, and now it’s being asked to approve another, even larger spending plan.

The looming PSC election has turned this from a regulatory proceeding into a political flashpoint. The race pits incumbents like Fitz Johnson, who frames the choice as one between “affordable, reliable energy vs. costly climate mandates and rolling blackouts,” against challengers like Hubbard and Alicia Johnson, who argue for more aggressive oversight and a pivot toward cheaper renewables. The rhetoric, particularly the "Don't California my Georgia" line, is politically effective but analytically hollow. It sidesteps the core financial question of whether natural gas is, in fact, the most affordable and reliable path forward, especially given its price volatility and the lengthy construction timelines.

The critique isn’t coming just from one side of the aisle. Robert Baker, a Republican who served on the PSC for nearly two decades, has publicly stated that the current commission essentially “rubber-stamps everything that comes its way from Georgia Power.” This isn't a partisan squabble; it's a fundamental debate about the role of a regulator. Should the PSC act as a passive approver of the utility’s plans, or should it proactively drive the agenda, as Hubbard suggests, and demand a rigorous, transparent comparison of all available options? The data strongly suggests the latter is not happening. When a utility has a clear financial incentive to pursue capital-intensive projects, an active and skeptical regulator is not a luxury; it’s a mathematical necessity to protect consumers.

A Calculated Miscalculation

When you strip away the political framing and corporate talking points, the numbers point to a single, disquieting conclusion. Georgia Power's $15 billion proposal appears to be a solution optimized for its own revenue model, not for the stated problem of meeting urgent demand in the most cost-effective way. The plan prioritizes the construction of slow, expensive, utility-owned assets over the integration of faster, cheaper, third-party renewables that are already waiting in the queue. This isn’t an accident; it’s a business decision. The risk is that this calculated choice will become a long-term financial miscalculation for the 2.8 million customers who will be paying for it for decades to come. The decision the PSC makes in December isn't just about kilowatts and data centers; it's about whether Georgians will be locked into another cycle of predictable cost overruns for a strategy that was arguably suboptimal from the start.